Fokus

Dormitórios

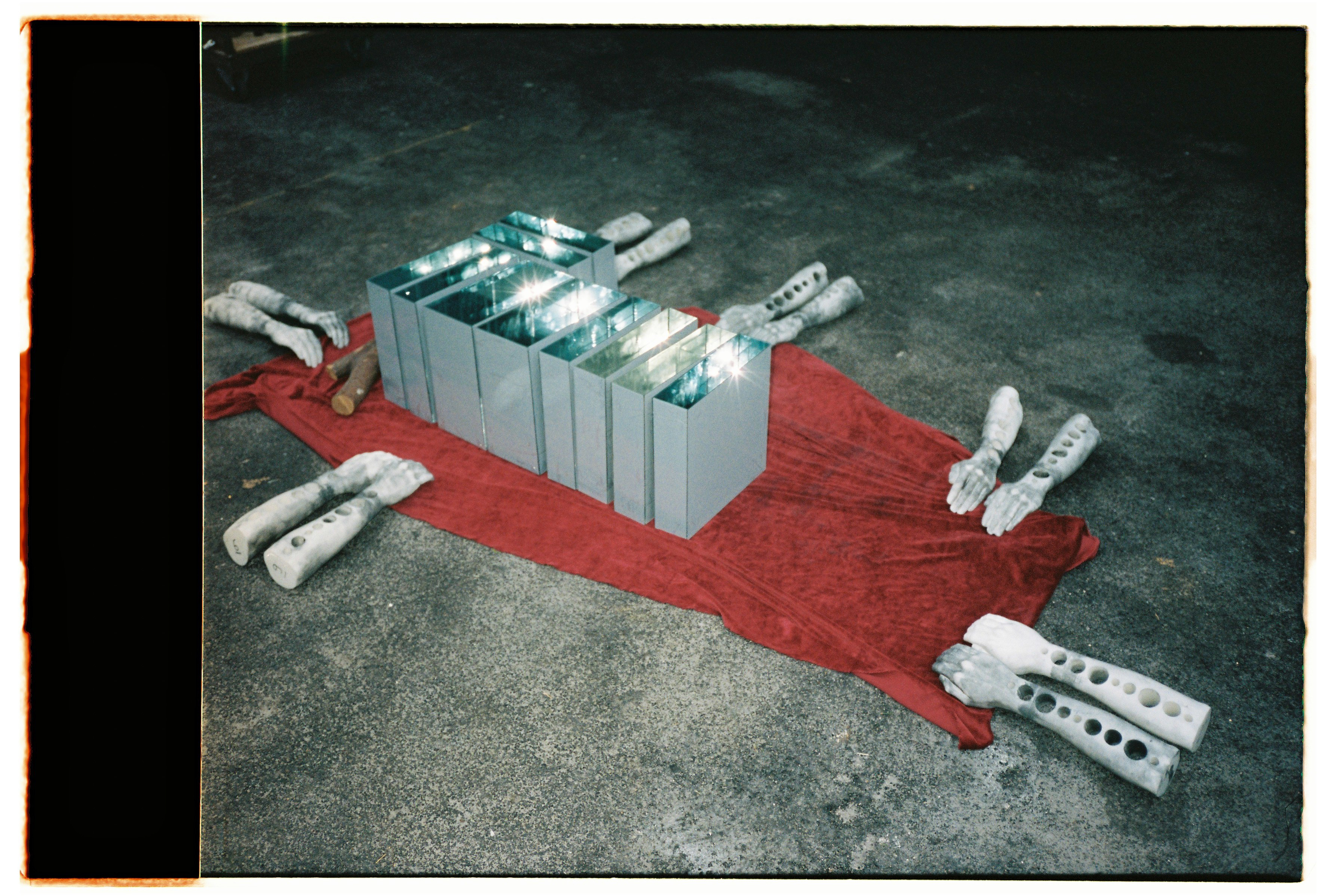

A rectangular structure is laid out on the floor of the Kunsthalle Arbon. Its shape recalls an archaeological excavation site, a labyrinth, or the floor plan of a house. The title of the exhibition adds further associations: a Dormitório is a bedroom or dormitory. In antiquity, cemeteries were also referred to as such: the ancient Greek word Koimeterion, from which the word "cemetery" is derived in many languages, essentially means a sleeping place. The cemetery, the sleeping place, the house, the ruin—these are spaces of personal significance for Paulo Wirz. In Brazil, he grew up in a house located next to a cemetery and a wasteland. Emptiness, death, and also Afro-Brazilian religions shaped his interest in how people develop rituals and customs to grapple with the fundamental themes of life. What myths and narratives do we create to cope with the unanswered questions of life, to find meaning and comfort? What kind of objects emerge from this practice? These are the kinds of questions that Paulo Wirz explores in his installations—much like an anthropologist.

In The Sacred and the Profane (1990), Romanian scholar of religion Mircea Eliade writes about how everyday objects become cultic through ritual acts. The sacred, he argues, does not lie in the object itself, but in how we engage with it—something Wirz has often observed in the religious practices of Brazilian Candomblé: jewelry, glasses, shells, and other everyday items are transformed into symbolic objects. Artworks, too, are such cultically charged objects, acquiring their value through a sophisticated system of value attribution—from medieval icons to modern masterpieces. Another key reference for Wirz is the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. In The Poetics of Space (1958), Bachelard explores what constitutes a house. For him, it is not the physical building that matters, but the entire network of memory, history, and imagination connected to the place.

Paulo Wirz's installation suggests a division into various rooms or spaces. However, it does not refer to any existing building. The spatial layout instead draws from various places the artist has lived. The objects that make up the structure also have their own histories. Many of them have already appeared in earlier installations by Wirz. All of them, in various ways, address the themes of transience and preservation and engage with the ambivalence of presence and absence, materiality and immateriality. They explore ephemerality and permanence, wholeness and fragility, as well as decay and conservation.

A thin red thread wraps around all the objects. In Greek mythology, Ariadne's thread served as a means to find one's way out of the labyrinth. The installation is titled Encruzilhada, which means a crossroads or a critical juncture at which a decision must be made. In Wirz’s installation, however, the thread offers no such guidance. It does not lead us to an exit; rather, it creates connections between the individual objects. Instead of offering us a way out of complexity, it draws us further into the entanglements between the sacred and the profane, between ritual and everyday action. In doing so, it traces a story of how humans respond to life’s challenges and the uncertainties of their world—a question that holds personal relevance, but also political urgency in light of today’s global crises such as war, climate change, and food security.

Paulo Wirz

Persönliche und gefundene Objekte, Zement- und Bronzeabgüsse, geblasenes Glas, Besteck, Glasbecher, Papierblumen, Baumwollfaden

Paulo Wirz

Persönliche und gefundene Objekte, Zement- und Bronzeabgüsse, geblasenes Glas, Besteck, Glasbecher, Papierblumen, Baumwollfaden